By Maria Jassinskaja

A friend of mine who recently went through a long period of uncertainty regarding his work situation noted an undesired side effect of this stressful time – his hair was going gray, way too fast to be considered normal aging. Indeed, the phrase “You’re going to give me gray hair!” implies a connection between someone stressing you out and premature loss of hair pigmentation. Plenty of anecdotal evidence exist for this phenomenon, but the biology behind it has long remained a mystery. Recently, a group of researchers at Harvard University set out to solve this long-standing question, and published their findings in the prestigious scientific journal Nature in January 20201. The answer? Stressed out stem cells.

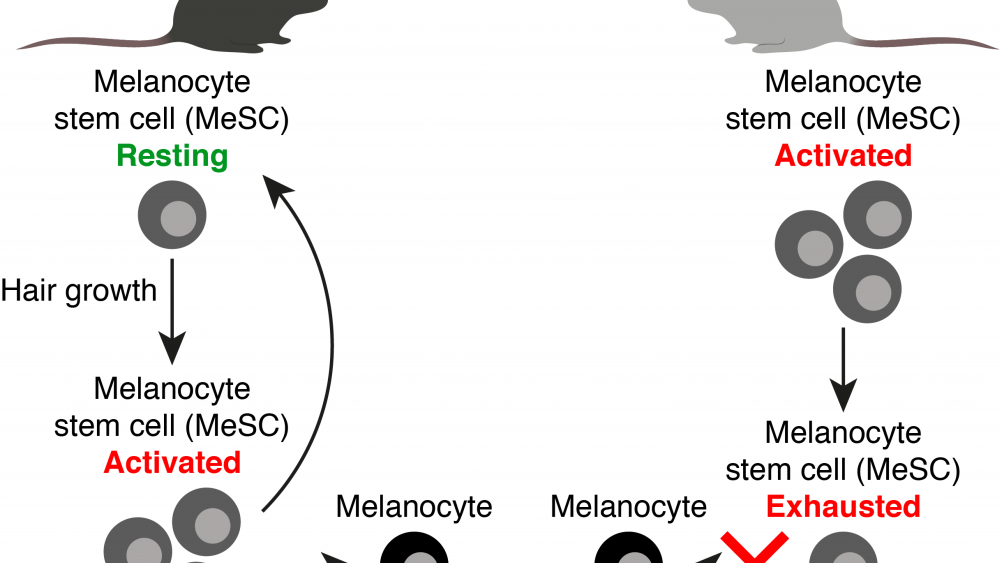

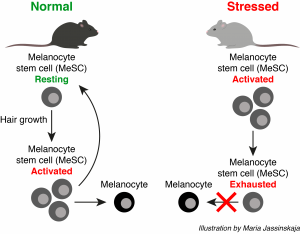

After a bad haircut, one can often find some consolation in the fact that hair (usually) grows back. Just like in many other tissues where we see this kind of regeneration (such as blood or skin), hair regrowth is made possible by stem cells – in this case, hair follicle stem cells (HFSCs). However, while HFSCs ensure that we don’t go bald, they have little to do with the actual color of the hair. The color, or pigment, in hair comes from another set of stem cells – the melanocyte stem cells (MeSCs). Just like most other adult stem cell types, MeSCs are normally in a resting stage, which protects the cells and ensures their longevity. MeSCs are activated during hair growth to divide and produce mature pigment cells (melanocytes) which give our hair (and skin) its color2. Depletion of MeSCs with age has been suggested to be the reason behind why humans (as well as other animals) go gray as we approach our golden years3.

In the Nature study1, Zhang and colleagues found that stress caused the fur of black mice to become white significantly faster than in non-stressed animals. This effect was most pronounced when the stress was caused by pain, but was also evident when the stress was caused by restraining the animals or subjecting them to so called chronic unpredictable stress, such as quick switches between isolation and crowding. Upon closer examination of the cells responsible for hair growth and pigmentation, the researchers found that while HFSCs were unaffected by stress, MeSCs were quickly depleted from the hair follicle. In other words, the hair of the stressed mice grew out as normal, but had lost its black color. This was due to an abnormal increase in the rate at which the MeSCs divide, which caused the pool of stem cells to gradually become depleted and finally disappear. This in turn lead to a complete and permanent loss of pigmentation in the affected hairs. The main culprit behind this effect turned out to be noradrenaline, which is the hormone responsible for initiating a fight-or-flight-response in animals faced with danger. The secretion of noradrenaline was caused by stimulation of the sympathetic nervous system, which is part of the autonomous (unconscious) nervous system and is responsible for sensing and responding to danger. Molecularly, human MeSCs responded similarly to the mouse cells, indicating that noradrenaline may have a similar effect on human hair pigmentation as it has in mice.

Although there is a lot of evidence that these biological processes occur also in humans, one should keep in mind that this study was done mainly in mice. It is difficult to translate the stress experienced by the mice into human stress factors. Are a couple of bad weeks at work enough to damage human melanocyte stem cells permanently, or is a much more severe type of stress required to produce this, often undesired, effect? Regardless of the exact mechanism, stress has previously been shown to negatively affect other adult stem cell types, such as hematopoietic stem cells4, which can potentially lead to much more severe side effects than a couple of unwanted gray hairs. With that in mind, enjoy a lazy summer vacation this year – your stem cells could really use a break.