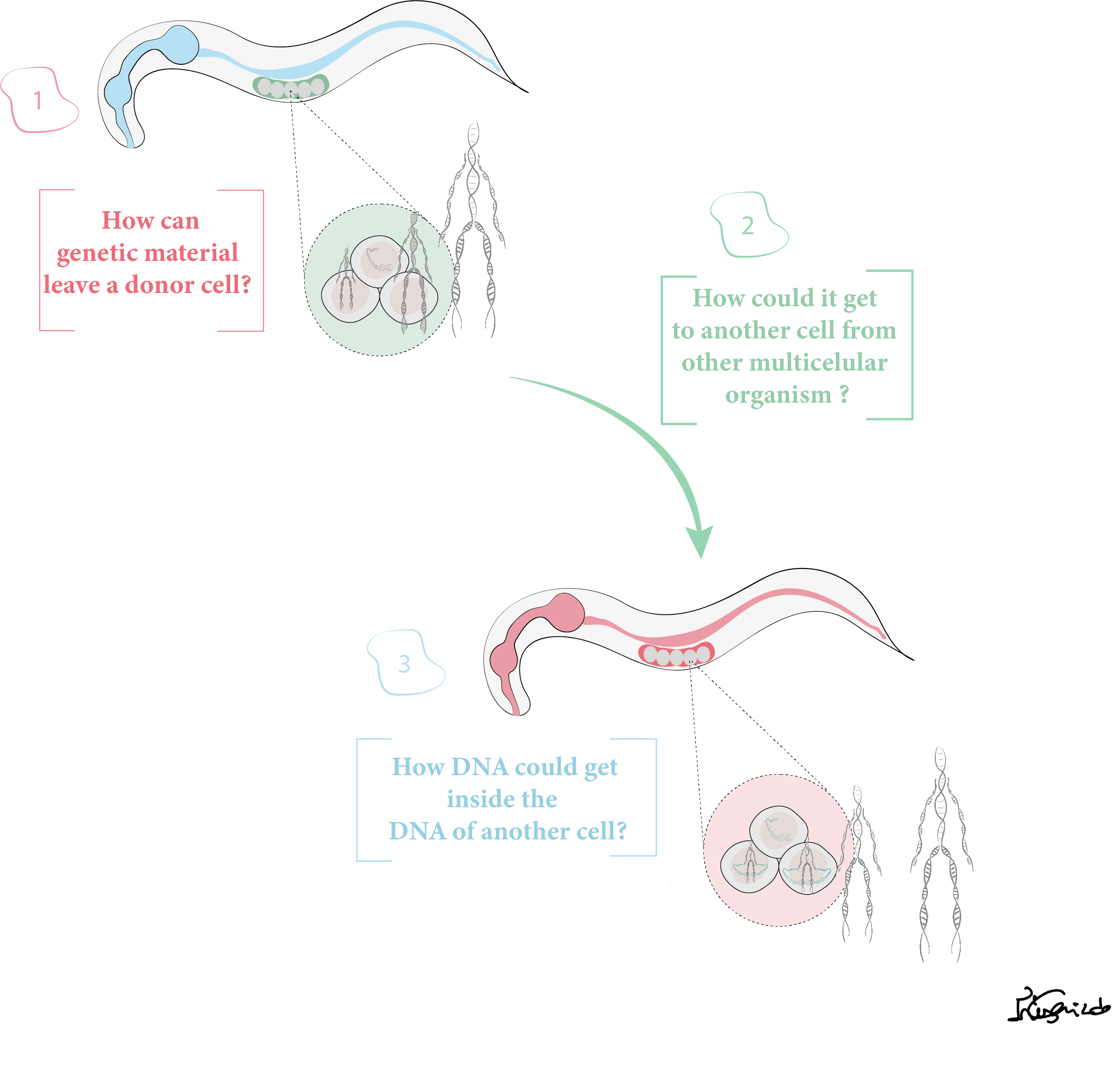

I bet your first thought when you hear “gene transfer” is creation of a little cute human being by combining genetic material of parents. And you are certainly right. That is so-called vertical gene transfer. Apart from it, there is also horizontal gene transfer (HGT). While well studied in bacteria, this non-sexual exchange of DNA helps bacteria adapt to a changing environment (check what is “DNA” in our last post). The concept of HGT in more complicated organisms might seem unlikely at first glance due to various reasons from a DNA perspective, logistically speaking. How could genetic material leave a donor cell? How could it get inside a germ cell – the one which gives rise to gametes – sperm and egg cells, and therefore can pass genetic information to offspring. Finally, how foreign DNA could be inserted into the genome of germ cells (genome is all the genetic information of the organism that consists of DNA or, in case of viruses, RNA)?

Examples such as the transfer of antifreeze genes between Atlantic herring and Japanese smelt enabling survival in icy sea waters, and the hijacking of plant detoxification gene by whiteflies to neutralise plant toxins underscore that HGT occurs even in complex organisms. Yet, the question of precisely how that happens remains.Here comes viruses, those invisible culprits responsible for our latest pandemic and the common cold. But what exactly do they do? They excel at grabbing pieces of DNA and inserting them into the genome of infected cells.

Adding a touch of complexity, or beauty, depending on your perspective, are the descendants of ancient viruses, known as transposons, “jumping genes”, “tiny genome travellers” (read more about them here). These elements populate large proportions of eukaryotic DNA and are termed “selfish” because their primary goal is to replicate, even if it means disrupting genes of their host.

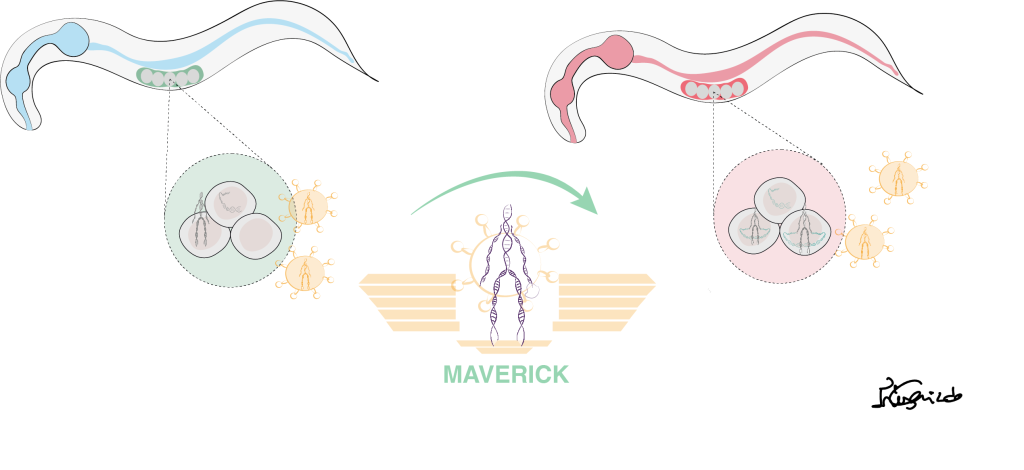

Now, let me introduce you to the stars of the show – Maverick elements – creatures that share features of transposons and viruses. Known already for many years but just recently discovered by a group led by Alejandro Burga in Vienna, Austria, as mediators of HGT in nematodes – tiny worms, only 1 mm long, that inhabit diverse locations worldwide. Due to their minimal dietary and living requirements, they are perfect organisms for laboratory studies.

Much like viruses, Mavericks have the ability to invade other organisms. Combining characteristics of both transposons and viruses, Maverick elements have been transferred between different worm species on a global scale, some of these events dating back to the era when dinosaurs ruled the world. In essence, the transferred cargo consists of genes that provide fitness advantage to offspring – a story awaiting exploration in the next post.

If you are now curious about whether the above findings hold true for humans, we still do not know. But hopefully, we will find out soon.

References:

Graham, L.A., Lougheed, S.C., Ewart, K.V., and Davies, P.L. (2008). Lateral transfer of a lectin-like antifreeze protein gene in fishes. PLoS One 3, e2616. 10.1371/journal.pone.0002616.

Xia, J., Guo, Z., Yang, Z., Han, H., Wang, S., Xu, H., Yang, X., Yang, F., Wu, Q., Xie, W., et al. (2021). Whitefly hijacks a plant detoxification gene that neutralizes plant toxins. Cell 184, 1693-1705 e1617. 10.1016/j.cell.2021.02.014.

Widen, S.A., Bes, I.C., Koreshova, A., Pliota, P., Krogull, D., and Burga, A. (2023). Virus-like transposons cross the species barrier and drive the evolution of genetic incompatibilities. Science 380, eade0705. 10.1126/science.ade0705.

Temp HotMail

Pretty! This has been a really wonderful post. Many thanks for providing these details.

Big News

Hey there, everyone! I just wanted to mention that I really enjoy reading this website’s posts and how often they are updated. It has nice things in it.