As we eagerly look ahead to 2025 and the scientific breakthroughs it may bring, let’s take a final look at 2024. In October the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was awarded to Victor Ambros and Gary Ruvkun. At that moment, the spotlight was turned on microRNAs (miRNAs) – tiny but powerful RNA molecules, whose discovery over 30 years ago reshaped our understanding of gene regulation.

First discovered in the 1 mm-long roundworm Caenorhabditis elegans (C. elegans)—widely used as a model organism in laboratories around the world, miRNAs quickly became recognized as evolutionarily conserved, meaning they are common in many different organisms, including humans.

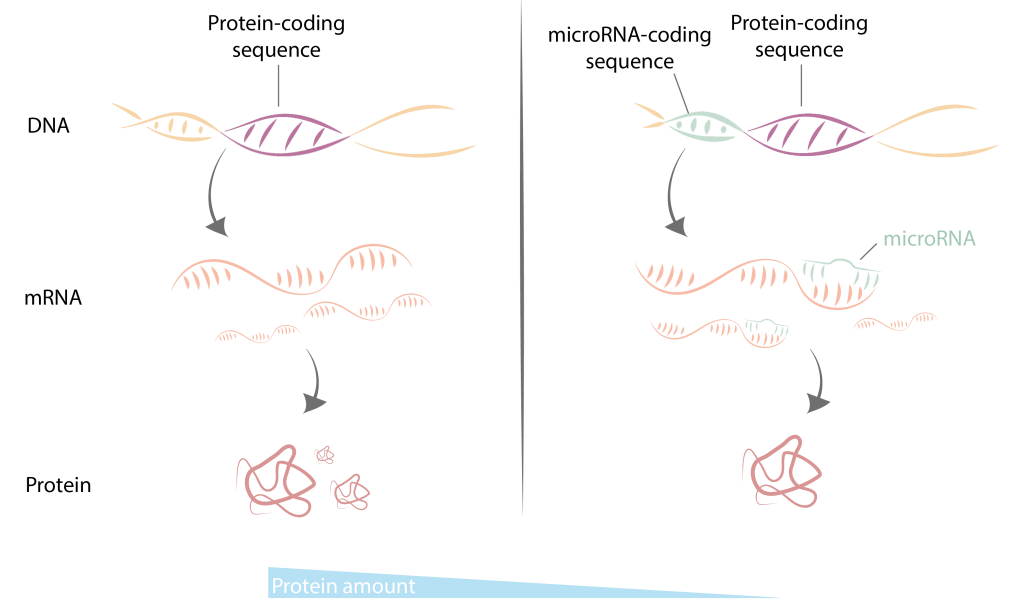

While the flow of genetic information from DNA to messenger RNA (mRNA), which is then translated into proteins, explains how the information in our genomes is expressed, it does not explain how our cells become so different from one another – like blood cells, neurons, or gut cells – or how we can fight viruses and adapt to a changing environment.

One solution to this puzzle is the regulation of genetic information at multiple levels, making certain genes more active in specific cell types or under different conditions. This is where microRNAs comes to play: a new type of very short RNAs, only 21-23 nucleotides long. Unlike mRNAs, microRNAs do not encode proteins. Instead, they bind to mRNA, preventing the translation of these mRNA sequences into proteins. In this way, microRNAs can control the amount of protein translated from a specific sequence of mRNA.

There are over a thousand genes encoding microRNAs in the human genome, and years of research have shown that cells, tissues, and organisms cannot develop properly without them. Any perturbations in microRNA expression or the cellular machinery responsible for their production can have deleterious consequences for an organism, potentially leading to diseases such as cancer, autoimmunity, or diabetes.

The discovery of microRNAs has not only transformed our understanding of gene regulation but also positioned microRNAs as potentially valuable therapeutic targets and diagnostic biomarkers. Some biotech companies are working to develop therapies that can mimic or silence microRNAs in diseases where their function is compromised. However, challenges like off-target effects complicate the development of such therapies, making their widespread use still a long way off. Moreover, microRNA expression is specific to various diseases, including cancer. Analysis of microRNAs in patient samples not only enables early detection and more accurate diagnosis, but also may predict treatment responses. Indeed, microRNA panels are already available to clinicians.

From an unassuming worm to cancer diagnostics, this is the true beauty of science. To read the full story behind Nobel Prize-worthy discovery of miRNAs, visit: https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/medicine/2024/press-release/